Office Evolution through the Intertwining of People and Spaces

Scroll Down

Nikken Group has undertaken its workplace-model test projects based upon the concepts of “revolution,” “experience,” and “carbon neutrality.” “Revolution” refers to Nikken Group’s efforts to ambitiously experiment with its own environment; “experience” concerns endeavors to enhance workplace value through joint, shared, and co-creation undertakings; and “carbon neutrality” is about endeavors for achieving net-zero carbon emissions.

With these keywords in mind, Shunichi Sugiyama (pictured left), a representative board member of Nikken Sekkei, sought insights from Ryusuke Naka (pictured right) about what new workplace models are called for today. Through his company Naka Lab. LLC, Naka explores ideas for next-generation workspaces together with companies and associations.

Ryusuke Naka (Naka) I have mainly studied the relationship between the spatial environment of workplaces and human activity. I first became interested in research on office spaces in university, after joining the laboratory of Professor Soichiro Okishio, a leading authority on the subject. Originally, though, I wanted to become an architect, and initially I focused on “hardware.” I believed it was most important to study the tangible aspects of the office space itself. But through my research, I came to understand the importance of designing spaces that are most effective at facilitating users’ achievement of their objectives. I realized my work needed to encompass the concept of work styles—the “software”; so my research focus gradually expanded to include not only the design of spaces but also the work styles and activities of their users.

What I found, however, was that most office users in Japan are unable to give a clear answer when asked about their ideal office space and working style. Many of them care about their home, but not so much about their office. Nevertheless, the users themselves are the most capable of determining what is best for them, so I gradually began to run workshops to help them reveal the needs they might not be consciously expressing and encourage them to be proactive.

When considering how to improve workplaces, we must not forget that the protagonists of the story, if you will, are the people who use them. It’s not enough for the space itself to take over the limelight; it must also bring out the best in the workers and their relationships with each other. When a workspace and the work that goes on there are intertwined, more interaction takes place—it becomes an exciting place that sparks activity and initiative.

Workplaces Prompting Cultural Change and Evolution

In the traditional Japanese city office, the distinct divisions of work mean that while communication occurs vertically in the hierarchy of a given section, communication laterally among sections is rare. When we implemented the free address system, there was a notable drop in communication across the entire office for the first few months. But gradually, people’s natural instinct to chat with their neighbors took hold, which led to more and more lateral communication, ultimately transforming the entire office atmosphere. The intertwining and interaction of an office space with the activities of workers changes the entire mood of the workspace over time.

Some time later, when I asked about any problems with handling sensitive HR data, the staff member sheepishly replied that simply moving to a good spot solved his concerns. Despite the simplicity of this solution, he would not have thought of it in the previous office environment. As a general rule, people are constantly affected by the spatial setting, whether consciously or unconsciously. So when the two elements—people and space—start to intertwine, there are phenomenal, transformative benefits for both the people and the culture within the workplace.

Sugiyama I would say that the change in the culture of the workplace is almost like evolution. For instance, when different kinds of individuals come together, the combination of their unique genetic sequences results in new genetic sequences—a process essential to evolution. When a space promotes human activity, it generates encounters with new people, environments, and situations; this is how evolution occurs in the workplace.

Naka I couldn’t agree more. Right now, we need to be facilitating diverse types of activities in order to foster such evolution.

New Offices for the Transition to a Carbon-Neutral Society

Now, I’d like to discuss what types of office spaces we will require within the next decade. Today, we have to work on the premise that carbon neutrality is a requirement; as such, we are working on a new office concept and methodology that we call the “Next Generation Office Prototype.” The idea is to transform the conventional uniform long-span building design by putting pillars in the space between the windows and the center of the office, creating a “concentration zone” and a “communication zone.” By allowing for structural flexibility in the office perimeter areas, possibilities to create new spaces are born—for example, atrium spaces or wood-heavy spaces. By our estimation, this plan will lead to a 46 percent reduction in CO2 emissions by reducing the use of steel and concrete, which account for the lion’s share of CO2 emissions at the construction stage.

Naka There’s basically a proportional relationship between the size of an office and how high its rent is, as many organizations are aware of the value of mixing people in a shared space. But instead of having spacious floor areas, connecting upper and lower floors with an internal staircase or atrium can lead to both more freedom of movement and increased opportunities for communication, and in that sense, it can be more cost-effective compared to the large-office space. It’s a good thing, right from the beginning, to leave room for improving the office environment according to future changes in circumstances.

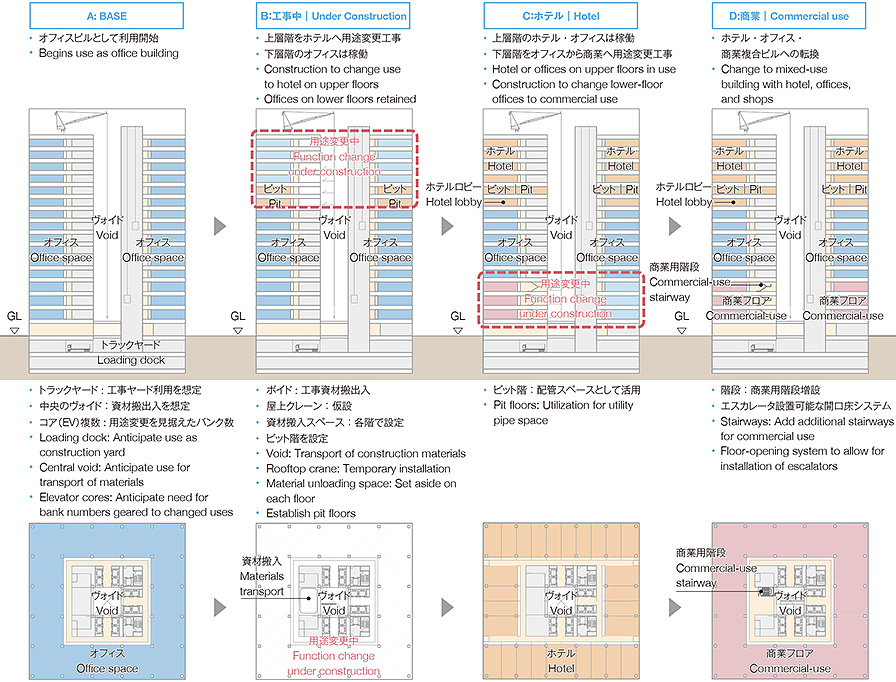

Sugiyama Something else we’re working hard on is the “Life Cycle Box,” which makes it possible to smoothly transition the use of a building—from an office, say, to a hotel or retail store. Buildings get demolished primarily because they become outdated in terms of their adaptability and their facilities and functions—not because of the service life of their skeleton. That’s why we developed a model that can, from the time a building is constructed, anticipate solutions to the challenges that building-code restrictions present to renovation efforts.

The Life Cycle Box also addresses another challenge during renovation: carrying out construction work while tenants still occupy the building. In this model, voids and pit floors, which can also be used for carrying in materials, are installed at the time of initial construction along with an underground parking area, which serves to facilitate the construction flow line during renovation. The premise is that taking such measures in the initial planning stages will promote building renovation, lengthening the lifespan of the building and helping to reduce CO2 emissions.

The “Life Cycle Box”: Visualization of future changes in the use of offices

The “Life Cycle Box”: Visualization of future changes in the use of offices

Sugiyama I think the key to achieving carbon neutrality from here on is to arrange these types of mechanisms at the outset of projects. Our aim is to gradually bring the proposals we’ve been discussing to realization going forward.

“Living Workspace” where People and Activity Come Together

Naka I think people are more motivated and creative in their work when diverse activities are combined.

“Living Workspace” is a small workspace located at the edge of Lake Biwa. Before beginning the project, I spent about a week working remotely from a guest house near the lake as a kind of experiment. After a few days, the owners asked me to help them chop firewood. Under normal circumstances, I would have told them I was busy with work and politely refused, but living in a natural environment makes one inclined to cooperate in such ways. It was really wonderful to experience that. I would go for a swim in the lake during breaks from work. I came to realize that working in a place where I could easily mix non-work-related activities into my daily routine had a very beneficial effect on my productivity.

It was from this experience that the “Living Workspace”—a space that creates harmony by bringing together various different people and activities—was born. Going forward, our aim is to not only mix together various activities but also encourage interaction between urban office workers and people like local farmers and fishermen, who have traditionally had little opportunity for such contact. This will surely give rise to exciting new ideas and business opportunities.

“Living Workspace” project (Courtesy of Naka Lab)

“Living Workspace” project (Courtesy of Naka Lab)

Now, this is a little off-topic, but I’d like to mention the Toyosu Civic Center in Koto Ward, Tokyo—a design project we completed in 2015. It’s a complex that houses a branch of the local ward office, a library, and a hall, among other facilities. For this structure, we proposed a hall that can “open up” its rotating panels—both on the wall at the rear of the stage and to the right of the audience seats—to reveal the Toyosu seascape behind the stage. Despite the initial skepticism toward the unprecedented design, the musicians and performers who use the completed hall find the panels intriguing; they even came to incorporate the open-and-close feature into their performances. This was a very positive intertwining that emerged between a space and its users.

Sugiyama I agree. The idea behind our proposal was that if we trust the users and give them free rein with the hall, they might come up with new ways to use the space.

Naka On top of the significance of bringing together activities and people in the workplace, another essential thing to consider is the concept of change. Recently, I’ve been promoting a work style called “outside work.” The modern office worker has become accustomed to an office environment that is kept at a comfortable temperature and humidity level throughout the year, but change is essential for keeping the mind active. Allowing our activities and our mood to change in synch with the outdoor environment has a positive effect on our work.

Sugiyama Putting ourselves in the same environment day in and day out weakens our resilience.

Personally, I’ve been thinking that when planning an office space, it might be interesting to gather datasets on the workings of a day in an office and compare them with fluctuations in energy consumption. In recent years, there have been increasing efforts to design non-uniform and unique spaces—instead of homogeneous ones—with varying air conditioning and lighting levels. I think the key to creating such spaces lies in measuring people’s daily behavior from various perspectives.

Naka I believe it’s important for people to develop a healthy tolerance for change, and it also is crucial to create spaces that can adapt to that change. In the case of cities, however, urban spaces and their architecture are designed to accommodate the finely fragmented functions of social systems, so it’s difficult to create opportunities for change that involve an intermingling of various activities.

Sugiyama That’s true. Such systems can greatly constrain human behavior. When designing urban spaces and architecture, therefore, it’s important to avoid laying down too many rules and also to question existing rules.

Naka Yes, I agree. Regarding such restrictive urban spaces and architecture, which create clear divisions of use to prioritize economy and efficiency, the architect Shoji Hayashi (a former executive vice president of Nikken Sekkei) once said, “Architects have been making mistakes for 100 years—mistakes that we will spend the next 100 years fixing.” I hope that even in urban areas, we will see more and more spaces that facilitate the intermingling of various types of people and activities.

Ryusuke Naka

Representative, Naka Lab

Professor Emeritus, Kyoto Institute of Technology